Back to blog

Blog

10/18/2019

Restoring Michael Pica's 1949 D'Angelico Excel

Justin Friedman is the Director of Marketing & Artist Relations here at D’Angelico Guitars. He’s been a part of the D’Angelico family for three years. We’re overjoyed for him that he was able to make one of his lifelong dreams of owning an original D’Angelico come true. He truly deserves it!

____________________

When I was 14 years old, I had the audacity to audition for the advanced guitar club at my high school. It was run by Joe Carbone, an old-school Italian-American who looked like more of a relic from the 1920s than a schoolteacher. He was short and stocky with a thick white mustache. He always wore a custom, perfectly-tailored suit with designer cufflinks, a shiny diamond pinky ring, and handmade leather shoes—all topped off with an italian Borsalino hat. Some people called him the Don Corleone of the school while others actually believed he had secret ties to the Italian Mafia. In the confines of my New York high school, he was the boss.

After several attempts at auditioning, Mr. Carbone finally let me in the club and that’s where our relationship began. Over the next five years, Carbone took me under his wing and became a mentor to me. He taught me everything he knew about the guitar. He educated me on the history of the instrument and all the forgotten masters who once wielded it—guys like Johnny Smith, Joe Pass, Bucky Pizzarelli, and Tony Mottola. One day, Mr. Carbone called me over to his office and said, “J, I gotta show you something.” He ushered me over to the closet where inside lay a beat-up brown leather guitar case. He told me to open it, and with amazement, I pulled out his 1937 D’Angelico Style B. The sound and look of that guitar changed my life forever. It carried with it the history of New York and of the old shop that once stood on 40 Kenmare Street where John D’Angelico practiced his craft. “I could play this guitar acoustically through an entire horn section” Carbone said. “That’s the magic of D’Angelico guitars. They project, they cut, they have that sound.”

Joe Carbone (left) and his 1937 Style B visiting the D’Angelico Showroom with jazz guitarist Peter Rogine (right) in 2016.

_______________

I never forgot that guitar in the years after graduating high school and attending college in Connecticut. In 2016, I decided to move back to New York to pursue a career in the Music Industry. I was interviewing at places like Atlantic Records and Spotify, in hopes of balancing a job in the industry with my passion for playing the guitar. I didn’t exactly know how that balance would work, but I knew that my days of being around guitars for five hours a day would probably be over.

One day at the end of the summer, I was driving down the West Side Highway and saw this giant D’Angelico guitar on a billboard. The next week I saw a green room filled with D’Angelico Guitars at a music venue in Montauk. I didn’t know how this was possible. To my knowledge, John D’Angelico had passed away in 1964—what was this all about? A quick google search brought me to the D’Angelico website where I saw that the brand was back and making guitars again. The guitars looked impressive, and it immediately transported me back to those days with Mr. Carbone and my 15-year-old self staring into the windows on the top floor at Rudy’s Music in Soho looking at the D’Angelico’s in the glass cases…

I turned to my mother and said, “This is where I want to work.” She laughed thinking there was no way I’d ever actually work there. But I was determined to try. Right away, I pulled up the contact form at dangelicoguitars.com and wrote them an email.

After a few days of waiting, I finally heard back from an employee at D’Angelico. A couple of interviews later and a lucky opening on the Artist Relations team, and I was in.

But how does this relate specifically to original D’Angelico instruments like Mr. Carbone’s 1937 Style B? Well, for all of the privileges my job provides—working with jazz greats like Russell Malone and Mark Whitfield, rock legends like Bob Weir, and hanging backstage at music festivals across the country—what has and always will drive me to pour my heart into D’Angelico is the history. The real, forgotten stories kept alive by guys like Joe Carbone—the stories that are etched into the instruments that John D’Angelico built long ago.

About 18 months into my job at D’Angelico, a note was left on my desk stating that a gentleman by the name of Mike Lettera was looking to sell a 1949 D’Angelico that had been sitting in his closet in Arizona. To give you a sense of how rare original D’Angelico instruments are, here’s some context: Pablo Picasso made about 50,000 pieces of art in his career, and John D’Angelico only built 1,164 instruments. I remember an article in Guitar World about the 1942 D’Angelico Excel that was found inside an abandoned 1963 Cadillac in the backroads of Maryland, but I’d figured that was a one-off fluke. How many more of them could be out there?

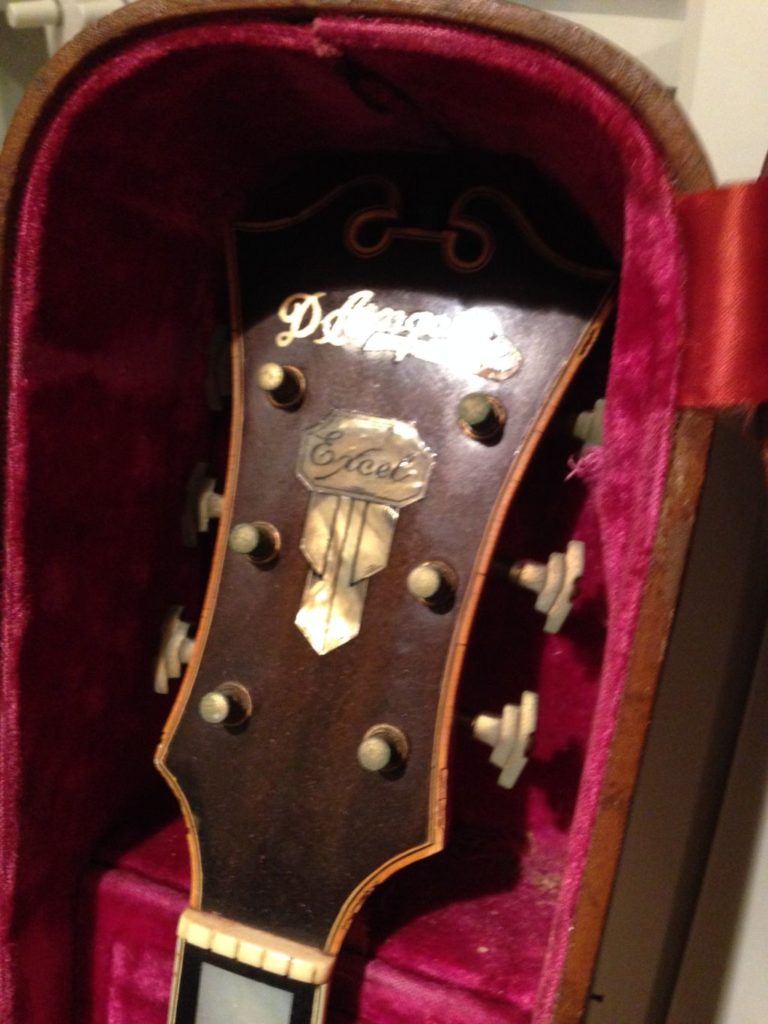

After calling Mr. Lettera back, I found out that the guitar was owned by his grandfather, Michael James Pica, before it was eventually passed down to him by his father. He emailed me photos, and I saw that the guitar (a blonde cutaway) was in terrible condition. The top had several cracks, the bridge and pickguard were missing, and the binding (which holds the entire guitar together) was almost entirely corroded. “It hasn’t had strings on it since my grandfather played it in the late 70s,” Mike told me. “It was his most loved possession and has been in my family for over 60 years.” It was clear that what I saw in these photographs was not just the shell of a once great guitar, but the memories of Mike’s grandfather and his early childhood.

Original photos that Mike Lettera emailed me on December 27th, 2017 of the 1949 D’Angelico.

_______________

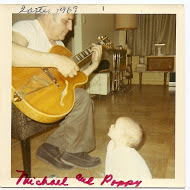

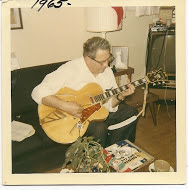

Michael James Pica (known as Poppy to his grandchildren) was a welder for the city of New York and family man from the Bronx who saved every penny he had to buy this guitar from John D’Angelico in 1954. According to the original receipt (which Mike sent me a photo of), the guitar was actually built for a gentleman named Sal Constantino in 1949, who is said to have used it frequently on The Martha Raye Show. Sal eventually traded in the Excel (likely to upgrade to the newer ‘New Yorker’ model) and then Michael purchased it used from D’Angelico’s shop for a whopping $200 paid in full on May 15th,1954. Once the guitar came into Michael’s possession, he and his family cherished the instrument for over 30 years, playing it at home after work and at late night family dinners in the Bronx.

He was a hobbyist. Poppy had this darkroom in the basement where he was into things like photography, model trains, pigeon racing and later into raising tropical fish. He always had a thing. And the guitar was always his thing. Never professionally, but just as Poppy. At Easter time, all us kids would listen as Poppy would just sit and play the guitar and dance around. I remember their house in the Bronx had all wooden floors so it was always fun because my cousins and I could spin around and dance. – Mike Lettera

Michael James Pica with his guitar in 1965, 1969 and 1971 respectively. Note: By 1969, the pickguard and DeArmond pickup were missing.

_______________

According to his grandson, Michael was a lover of jazz and played tunes like “If I Had You,” “Give Me The Simple Life” and “Round Midnight.” He admired the players that Carbone admires, guys like Tony Mottola, Bucky Pizzarelli and Joe Pass—the New York guitarists that frequently hung around John D’Angelico’s shop.

After nearly 25 years of cherishing the instrument, Michael grew sick from lead poisoning, and after a heart-attack in 1978, he and his wife decided to move to upstate New York to be closer to his relatives. It was then that the guitar stopped being played and started to deteriorate physically as it sat in the basement of his house. Michael’s grandson recalls that the basement in upstate New York had surface mold and the case was found sitting on wet cardboard. Eventually, Michael decided that he didn’t have the money to get the instrument restored, so he passed the guitar down to his son-in-law Saverio ‘Sal’ Lettera in 1990. Sal was a Postal Worker in Fort Apache and while he did play guitar, he could not afford to restore the guitar properly. So in 1991, when his son was visiting him from Arizona, he passed the guitar down to him thinking that the drier climate out west would better preserve the instrument.

That summer, Mike drove the guitar in the front seat of his car from upstate New York to Tucson, Arizona where the guitar stayed in his possession, untouched for nearly 30 years. “It usually sat in the closet or on the shelf,” he said. “My sons don’t have an interest in guitar playing, and I don’t think they see the fact that my Dad’s got an antique and we should fix it.” Mike eventually decided that the guitar had no more use in his family, and in December of 2017 reached out to us at D’Angelico, hoping to find a buyer for the instrument.

I couldn’t believe what had showed up in my life—I knew that this might be my only chance to buy an original D’Angelico. Knowing full well that I would do anything I could to purchase the guitar, I played it cool for a while. I sent the photos of the old D’Angelico to my friend Larry Wexer, who used to work at the acclaimed Staten Island guitar shop Mandolin Brothers, for appraisal. He told me that, if restored, the instrument could be worth up to $25,000, maybe higher. He advised me that while the guitar was in absolutely horrific condition, the Birdseye Maple that made up the back and sides of the guitar was a less common choice for D’Angelico and therefore gave the instrument extra value.

What struck me was not only the instrument, but the story that it carried, and the need to save this rotting guitar from a closet in Arizona and bring it back to the city it once came from. I told Mike my story, my memories with Mr. Carbone and my two years of being a part of the team that was working to bring back the D’Angelico name. I professed to him that owning an original D’Angelico had been a lifelong dream of mine and that I would do anything in my power to get the guitar restored and cherish the instrument for a lifetime. I made him an offer on the guitar and after a few phone calls and email exchanges, we came to an agreement.

Finally, on March 14th, 2018, I purchased Michael Pica’s 1949 blonde D’Angelico Excel. When it arrived at the D’Angelico showroom a couple days later, the condition was even worse than I had thought. The binding was so corroded that the top of the guitar was almost fully detached from the body, and some of the cracks that I made out in the pictures were far worse and far bigger in person. But despite all of this, the guitar still had an indescribable aura to it—an almost magical look like it wasn’t even real. The wood was aged and had a kind of surreal definition to it as if the countless cigarettes that Michael Pica smoked in his small apartment in the Bronx gave it a smoky tint.

1949 Excel arrives to the D’Angelico Showroom on March 16th, 2018 prior to its restoration.

Note the binding corrosion on the right photo.

_______________

But before this guitar could be played and cherished, it needed to be saved. And there are only a few people in the world who are qualified to take on a D’Angelico restoration of this magnitude—the best being master luthier Chris Mirabella of Mirabella Guitars.

At the time, Chris’ showroom was located behind a pizza shop in Amityville, New York. When you walked into the place, you were instantly taken back 50 years and welcomed by two short and stocky Italian gentlemen who would ask a bunch of questions before allowing you to see Chris. Their ‘standoffish’ personality was quickly swayed when I told them I had an original D’Angelico in the case and was a friend of Joe Carbone’s (a steady client of Chris’). “Chris has worked on over 500 D’Angelico’s in his career,” one of the guys told me. “That’s nearly half of the D’Angelicos John ever built—he’s the best there is.”

Chris, now an acclaimed builder himself, started working with guitars at the age of eleven when he held an apprenticeship in Long Island, assisting with the construction and restoration of fine stringed instruments. It was during this time, in the early 1980s, that he was exposed to and influenced first-hand by the talents of James D’Aquisto (apprentice to John D’Angelico), as well as master luthier John Monteleone. When I was finally brought in to see Chris and showed him the guitar, the first question I asked him was, “Why do so many original D’Angelico guitars deteriorate over time?”

It’s a regrettable situation we now see with the original binding on many D’Angelico instruments. Just like with their original pickguards, the original celluloid binding, most likely in a reaction with the acetone-based glue which was used to apply it, over time reacts and starts to destroy itself. This destruction begins with small cracks notable on the binding, which then release a gas and corrosive film that rapidly attacks the binding, infecting the contacting cell structure of the wood, breaking down the glue joints of all nearby areas as well as tarnishing and oxidizing all the metal parts of the guitar. Simply put, left unattended it can have devastating and in some ways irreversible results. Leaving the instrument with blotch-like stains on the lacquer finish near the binding line, complete separations of the back, top and sides. The gold plating of the metal parts can be entirely eaten away and even eroded and pitted by the gas. – Chris Mirabella

Chris also suggested that it should be understood that the choice of using an inferior material was not the fault of John D’Angelico—it was simply not anticipated that the problem would show itself so many years after the instrument’s original creation. D’Angelico ran a small operation relative to his competitors and sourced all of his materials locally.

So we learn, as makers, to develop new ideas and different methods to avoid these issues which plague the instruments of earlier masters and at the same time we restore, to allow these instruments to continue to be played, inspire and tell the stories of their owners, players and builders. – Chris Mirabella

Chris Mirabella inspecting the guitar at his showroom on March 17th, 2018.

_______________

Chris told me that the guitar could be restored but it would take 12 to 14 months. He advised that restorations of this degree must be done delicately and slowly to ensure the safety and longevity of the instrument. With some reluctance, I left the guitar with Chris. And over the next year, he did a complete rebind of the guitar, a full neck reset, crack repairs, spray touch-ups, a full re-fret, built a new replica pickguard and a full parts cleaning. Then on September 17th, 2019, nearly 18 months after I purchased the guitar from Mike, the guitar was ready.

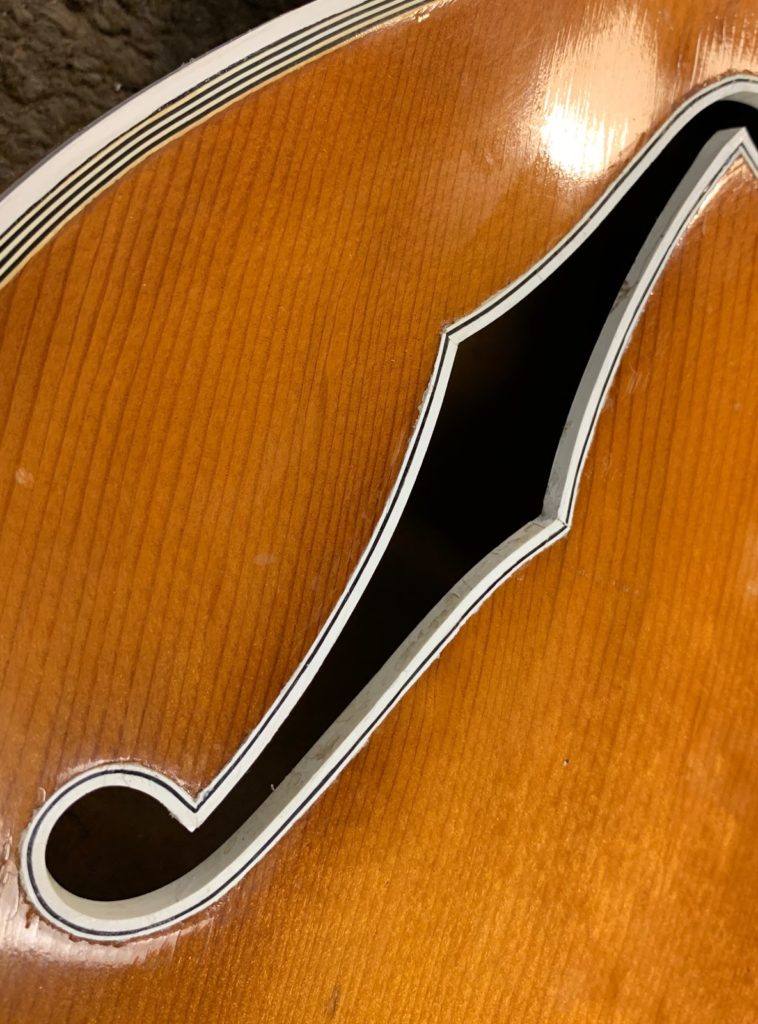

Photos of the guitar midway through restoration, after the guitar was rebound. Photos taken by Chris Mirabella.

_______________

The next morning, I drove out to Chris’ shop with my dear friend and NYC jazz guitarist Faton Macula to pick up the instrument. When Chris opened up the case, what I saw was beyond words. It was as if I had walked into D’Angelico’s shop in 1949 and picked up the guitar new from John himself. The guitar was restored to all its former glory. I picked up the instrument and played the first few bars of the popular standard “On a Clear Day.” The guitar sang and I heard that crisp, cutting sound that Carbone referenced years before. They were the first notes that had been played on the guitar in almost 40 years. “Whatever you like about her now, you’ll love a year from now,” Chris said. “And then wait 5 years—you’ll really see how she opens up. She’ll remember how to be a guitar again.”

Visiting the Mirabella guitars showroom with Faton Macula to pick up my guitar on September 18th, 2019.

_______________

Just a few days ago, I spoke to Mike Lettera to let him know the restorations were done.

Doesn’t it really feel to you like it’s a whole story? It’s the real deal, it’s what should be happening to this guitar. And the value was always there, I don’t care if it was worth $1,000 or $100,000, to me it’s a complete story… You’re probably one of the few people your age who have an interest in classic [pieces] where you would actually move forward and buy something. I work in car restorations, tile fitting, and mason work and it’s a dying trade. You see generations pass and you tell someone this guitar was built by a luthier and I don’t think they know what it even means. – Mike Lettera

I drove the guitar back to my apartment in Brooklyn, and took her to the D’Angelico showroom a few days later. I sat with the now restored guitar surrounded by hundreds of newer D’Angelico’s that inhabited the showroom. John D’Angelico’s photo stared down at me from the wall, and I knew in that moment that D’Angelico would live on forever.

A 2019 Excel EXL-1 model side by side with my fully restored 1949 D’Angelico Excel.

_______________

A special thanks to Mike Lettera, Chris Mirabella, Larry Wexer, Joe Carbone, Matt Brewester, Faton Macula and everyone at D’Angelico Guitars.